The English Prisoner Read online

Page 19

As we began our march down, the sick boys of Atrad 2 were filing out of the door to the shower room, their wet scalps steaming so much as they returned to the cold it looked like their heads were on fire. The shower I’d enjoyed the night I arrived in the Zone was a single, makeshift installation that the Africans had built in the boiler room. I’d not been in the main shower room, but for some reason I’d been expecting to walk into the kind of shower area you find in a municipal sports centre, with benches and pegs and rows of shower-heads around the walls. Hope sprang eternal. The reality was quite different, and my heart sank as soon as I walked in – or squeezed in more like.

The room, no more than twenty-five feet by twenty-five in total, was divided into two with a changing area by the entrance and the showers beyond, and there was barely a square inch of floor to be found. The twenty or so pegs above the benches around the walls had all been taken, and everyone else was crammed into the middle of the room, trying to balance between the 100-odd bags of washing on the floor while trying to remove all their clothes and place them on top of the bags so they didn’t slide on to the filthy, slimy tiles below. The bodies were so tightly packed that we had to put a hand on each other’s shoulders to steady ourselves, and every time I bent over or pulled off a piece of clothing I felt my body rub up against someone else’s. The smell of BO, stale piss, shit and rotting feet was overpowering, and I stopped breathing through my mouth within seconds of walking in, in case I puked up.

‘And you Brits have always moaned about the Black Hole of Calcutta,’ said Benny Baskin, whose face appeared a few feet away when the guy between us bent over. ‘Welcome to the black hole of fucking Mordovia!’ he spat.

Clutching my dirty washing and a bottle of Fresh Cherry and Cotton Timotei shampoo to my chest, I joined the crush of naked bodies pushing their way into the tiny shower area, trying to make sure my rapidly shrivelling cock didn’t touch the backside of the guy in front. The Afghans, the only ones to keep their pants on, had monopolized one of the six shower-heads in the far corner. Everyone was washing their clothes as they washed themselves, but there was some kind of order behind the apparent chaos. There were four or five people standing in a circle around the other five showers fixed to the ceiling, and we took it in turns to stand under the stream of water to wet ourselves and our clothes. We then stood aside and lathered our hair, bodies and garments until it was our turn to go under the water again and rinse off. The water was beautifully hot, but nothing good came in Zone 22 without its price, and I shouldn’t have been surprised that the pleasure of feeling a sensation of warmth for the first time in a week was wrecked by the horrendous smell of mildly decomposing humans and the awkwardness of getting undressed, towelled and reclothed on a greasy floor while being pressed up against a scrum of naked murderers, rapists, muggers and cut-throats.

After the steamy heat of the showers, the cold outside came as a sharp jolt as we formed up and began to march back up the Zone. I could feel the freezing air getting to work on my wet scalp and by the time I reached the relative warmth of the atrad the moisture had turned to an icy sleet. I gave my head a vigorous rub with the towel before throwing it, together with my wet washing, over the hot water pipe in the corridor that ran down the middle of the building. When I had finished, Boodoo John, one of the Africans from the boiler room, was standing next to me holding a folded piece of paper. I’d been getting on well with Boodoo John; he was a gentle, unassuming character who seemed out of place in the Zone. He had a sympathetic, slightly sad expression on his face as he handed over the paper and said: ‘It’s from Papi.’

I quickly unfolded the paper and began to read the neat handwriting, in French: ‘Dear English friend, they’re taking me to Zone 19 for “treatment”. I will probably never see you again. If I do, I’ll probably be like Cosmos so avoid me at all costs! I enjoyed our chess together. It was my best week in the Zone in five years. Be good, my friend, and be careful who you trust. Stay out of trouble, remember everything I told you, and you’ll get out of here in one piece. If only I’d taken my own advice. Who knows, maybe I’ll see you in London one day and you can come round to our little terraced house? Best wishes, brother, Papi.’

‘Who’s Cosmos?’ I asked Boodoo John.

He shook his head before replying in his thick African accent: ‘Used to be one of Moscow’s top drug barons. Lived like a prince until they busted him live on Russian TV. They wanted to make an example of him so they sent him to Zone 19, zapped him with some volts and gave him some very uncool drugs. Now he’s in Atrad 3, half-vegetable, half-maniac. He’s the one with the eyes as wide as plates. Crazy Cosmos…’

21

Rakim, the Turk in charge of the horses and the delivery cart, was not popular in the Zone, and it wasn’t just that he looked like a cartoon cut-throat with his absolutely huge hooked nose, bushy black eyebrows, piercing cold blue eyes and bony face – a face crying out to be punched over and over again. He was a human being in the style and mould of Chan: a mean loner, who rarely spoke and never smiled. You could tell he was a wanker from 100 paces, and the fact that he was allowed to run errands outside the prison walls made him even more unpopular. What all of us would have given to be Rakim for a day and get out into the world beyond! Every day we watched him standing astride his open cart like a character from Fiddler on the Roof, as he trotted off through the prison gates to go to Leple village and fetch the sacks of grain and root vegetables, the urn of milk for the kitchen and the post.

As the rest of us lined up like the living dead at the main gates, waiting to be summoned for another day of deadly monotony on the factory floor, Rakim swept by and disappeared into the free world, the wind tugging at his clothes, with an extravagant flourish of the reins and a cry of encouragement for his horses. I suspected he timed his departure to coincide with our morbid march through the snow to the factory, and as the gates shut behind him and the sound of hooves and creaking wooden wheels faded into the morning air, we looked at each other, sneering, and shook our heads. He was clearly a fine horseman, but it wasn’t so much his equestrian prowess he was showing off – it was his independence. And that, to the rest of us, felt like a stab in the ribs.

One morning, Rakim was tending to the horses in the stable near the sewing factory as usual while we were all back in the atrads waiting for a new consignment of cloth to be delivered. I was standing in the corridor staring vacantly through the window of Ahmed’s office, wondering how to kill some more time, when three guards emerged from the admin building opposite and strode briskly towards the atrad. Usually they just ambled across alone or in pairs, so I knew something was up. We all stood up and took off our hats as they rushed through the entrance area and swept down the corridor into the dormitory. Moments later they re-emerged, with one of them holding up a medium-sized potato as if it was a trophy. It was an offence to keep food in the dormitories. We quickly put on our outdoor boots and shoes and hurried into the exercise yard, and a few minutes later we saw Rakim being frogmarched down from the stables in the factory area, back through the Zone gates and into the offices. A couple of guys chuckled to themselves, while the rest began to whisper excitedly. Rakim soon re-emerged with two guards on either side of him and immediately shouted angrily in our direction. It sounded like Turkish. The three of them turned right at the end of the building and began to walk diagonally across the compound to the far corner, towards the kennels and the solitary confinement block.

Boodoo John was standing next to me as we pressed up against the mesh fencing and watched Rakim being led away. Every ten yards or so, one of the guards shoved him in the back and he staggered forward, slipping on the compacted snow. As they approached the kitchen and canteen building, Rakim turned his head and started shouting abuse in Turkish in its direction.

‘He who seeks vengeance must dig two graves: one for his enemy and one for himself,’ said Boodoo John. ‘The snake himself has been bitten, and he deserves his pain after the trouble he has caused other

s. We won’t be seeing him for three months.’

‘Three months in solitary?’ I replied, in disbelief.

‘Rakim will survive. He’s strong and stubborn. He has learnt from his mules in Turkey. The last prisoner to get that long was not so lucky. A Vietnamese guy called Bao, who was always causing trouble. He went mad after a month and hanged himself with his bootlaces. We watched them take him out in a couple of brown sacks, one on either end, and it was Rakim who drove him out of here on the back of his cart. But Rakim will come out like he went in. Dead inside.’

I shuddered as I asked: ‘How many people die in here?’

‘Five have gone since I arrived four years ago. Two in solitary, two who were taken away and died in the hospital Zone, and one who died in his bunk in Atrad 2. It’s a good place to die, Mordovia – you’re halfway to hell already.’

I liked Boodoo John. There was a gentleness and serenity about him that singled him out from the rest. He went to the church service but he wasn’t a fanatic like Philip and some of the other Africans; he was quiet without being withdrawn; he worked hard and never complained. He wasn’t well educated like Ergin or Yevgeny the brainbox librarian, but there was a basic wisdom about him. Like the other Africans, he’d found it difficult to secure work in Russia and had turned to selling drugs to try and make a living. He wasn’t a scary, hardened career criminal, just an impoverished guy who had been tempted into illicit activity in order to put more food on his family’s table. It’s not easy being a poor foreigner in Moscow, and it’s even harder if you’re black.

‘So what’s the secret of avoiding trouble and getting out of here with body and soul intact, Boodoo John?’ I asked.

He thought for a minute and said: ‘Make yourself as invisible as possible. Back away from trouble. Work hard, and even the guards will respect you a little in the end. Help those you like where you can. Favours always get returned eventually. But don’t ask any favours from anybody. Let them do you a favour. Then you know you have a friend.’

It took a few days for the Zone’s jungle drums to reveal the full story of what had happened to Rakim. A raw potato was something of a luxury in Zone 22 and Rakim’s smelnik, Mehmet the cook, had placed one under his mattress and then gone to the admin building and told the FSB koom that the horseman had stolen it from the kitchens. The prison officials had as little time for Rakim as his fellow prisoners and they had no hesitation in condemning him to the cooler for the maximum period. The most shocking aspect of the episode was that it was his very own smelnik who had ratted on him. It was appropriate that two of the most malicious characters in the Zone ended up as eating partners, but that was only because they were Turkish, not because they were natural buddies. Over the months and years they had developed a seething hatred for each other.

No one knew exactly what had gone on between the two, but the universal suspicion was that as both of them were up for udo within the year, Mehmet had killed off one of his rivals for freedom in order to boost his own chances of getting out. The udo hearings in the local court came round every six weeks or so, and it was rare for more than a dozen to walk free at the same time. By stabbing Rakim in the back, Mehmet had climbed an extra rung or two up the ladder while sending his former smelnik towards the back of the queue with an additional six months nailed on to his sentence. As a ‘fuck-you’, it was a pretty impressive piece of work and I could only applaud his ingenuity in dispatching one of the nastier characters in the Zone. But it was disturbing all the same, and I realized I’d have to sharpen up and keep my wits about me at all times.

The one guy you were meant to trust in Zone 22 was your smelnik. By sharing your food and provisions with each other, you shared each other’s kindness and confidence. That was an unwritten rule: you don’t break the trust of the man with whom you break your bread. The incident with Rakim showed that even the sacred relationship between smelniks was not above violation.

Boodoo John gave me a gentle pat on the back and disappeared into the atrad as I headed for the smoking shelter and lit up a Marlboro. Ahmed was there and he smiled as I approached. We stood in silence for a while, hunched against the bitter wind, drawing on our cupped cigarettes.

‘So who’s it going to be?’ he hissed in a conspiratorial whisper. ‘Your smelnik, I mean.’

It was the third time Ahmed had asked me to be his eating partner in three weeks. A dozen others had made advances too, and it was starting to get embarrassing.

‘I don’t know, Ahmed, I still haven’t decided. Maybe I’ll just carry on eating by myself…’

He stepped a little closer and a cloud of steam and acrid smoke from his cheap cigarette shrouded his face as he spoke. ‘I don’t have much food to share with you, but I’m powerful in the atrad. I can make life easier for you. The guards like me,’ he grinned, making his long scar zig-zag across his face. ‘Forget the Africans. They cannot help you in here. I can protect you better.’

He was whispering so quietly I had to lean forward to catch what he was saying. That was how everyone spoke in the Zone. Only rarely did I hear an exchange take place in a normal voice at a normal volume. We spoke in pairs, muttering in hushed tones. You saw conversations, but never heard them. There was no ‘socializing’, no sitting around the kitchen table recounting tales of our former lives or discussing events in the Zone. Some of the Africans could be noisy on occasion, erupting into laughter or bantering with each other in the factory, but for the most part a sullen, suspicious silence hung over the camp. This was partly to avoid drawing the attention of the guards, who didn’t like the sight or sound of prisoners enjoying themselves or engaging in ordinary human activities such as communicating freely. But mainly it was because nobody trusted anyone else, except their smelnik and a handful of others with whom they’d built up a relationship over the years. Half the Zone were informers. The experience with Edik in Moscow, Papi’s insights into the ways of Zone 22 and the almost tangible air of conspiracy that pervaded the Zone like a fog had put me on red alert from the moment I’d arrived in the atrads. Only among the boiler-room Africans, who tended to stick together as a group rather than splinter into pairs of smelniks, did I feel comfortable. Otherwise, I trod warily and avoided contact with the others as best I could. It was information on a strictly need-to-know basis. ‘Be careful who you trust,’ that was what Papi said, and he’d repeated it in his note.

I smiled at Ahmed, trying to muster some feelings of brotherhood towards him, but it was difficult to warm to a man with a face like a butcher’s chopping board. I knew he had close links with the officials across the way, but whether that was an asset for me or a risk I just couldn’t decide. I looked around the exercise yard at the half-dozen other pairs of prisoners leaning towards each other so that no one else could hear what they were saying. Ahmed was no different from the others who’d come grinning and slapping me on the back and warning me who I could and couldn’t trust and telling me what a great guy I was and how England was the best country in the world and that David Beckham was the greatest footballer… He just wanted a share of my spoils, and I couldn’t blame him for trying when he had barely any provisions of his own.

‘Ahmed, I know I can trust you and I think you’re a good guy,’ I said, shuffling my foot in the snow and squirming inside. ‘I promise I’ll give you cigarettes and food when I have some spare, but…’ And the sentence trailed away.

‘I understand,’ he said, stubbing his cigarette out under his foot. ‘One day you’ll realize I’m a better man than I look.’

I wanted to call him back and try to explain myself better but he was away up the three steps to the door in a bound. I flicked my butt towards the atrad and it bounced off the wall in a spray of orange sparks. I spun round to see if a guard had witnessed what I’d done, then quickly went over and picked the stub up and put it in the bucket provided. As I walked back inside I saw Boodoo John directly ahead in the kitchen, preparing a bowl of foo-foo, a Russian version of a Nigerian dish, made with soggy s

oda bread instead of the traditional yams.

‘I know you said I shouldn’t ask favours of other prisoners, and I’ll make this my first and last. Will you be my smelnik?’

Boodoo John put down his bowl and said: ‘I won’t be able to offer you any food, or coffee or cigarettes, but what I can offer you is my confidence and my loyalty. It would make me very happy to be your smelnik. Thank you, brother.’

*

I wasn’t bothered that Boodoo John didn’t have much food to share with me, because my supplies had been replenished a couple of weeks after I’d been transferred to the atrad in an incredible act of generosity by Alexi, one of my former Russian clients. Alexi, a great kindly bear of a man who’d looked after Mum, Dad and Lucy when they’d come to Moscow, had made the twenty-four-hour round trip from Moscow in terrible weather to bring me a second box of staple provisions and cigarettes. He’d bought all 200 pounds’ worth of it with his own money, not to mention the petrol, but I never got to see him and thank him because the bastards in the offices said he had failed to make a visitor’s appointment, and he had to get straight back in his car and make the long journey home through the night.

The mercy run came just at the right time, because my reserves of food and cigarettes were almost exhausted. I’d been expecting a visit from the British Embassy, but the severe weather had discouraged them from risking the journey. Unknown to me, though, Alexi had braved the conditions to get some supplies to me, and within minutes of it arriving that afternoon the news had swept around the factory. Whenever I looked up from chalking the buttons, there was always at least one guy on the sewing machines smiling at me, and when we filed out of the building at the end of the shift I was escorted by a small posse of grinning, backslapping wellwishers, eager to remind me what a nice, kind Englishman I was and what a brilliant country I came from.

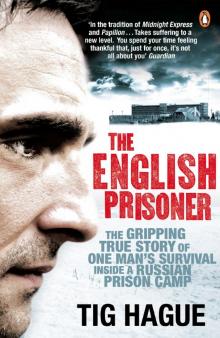

The English Prisoner

The English Prisoner